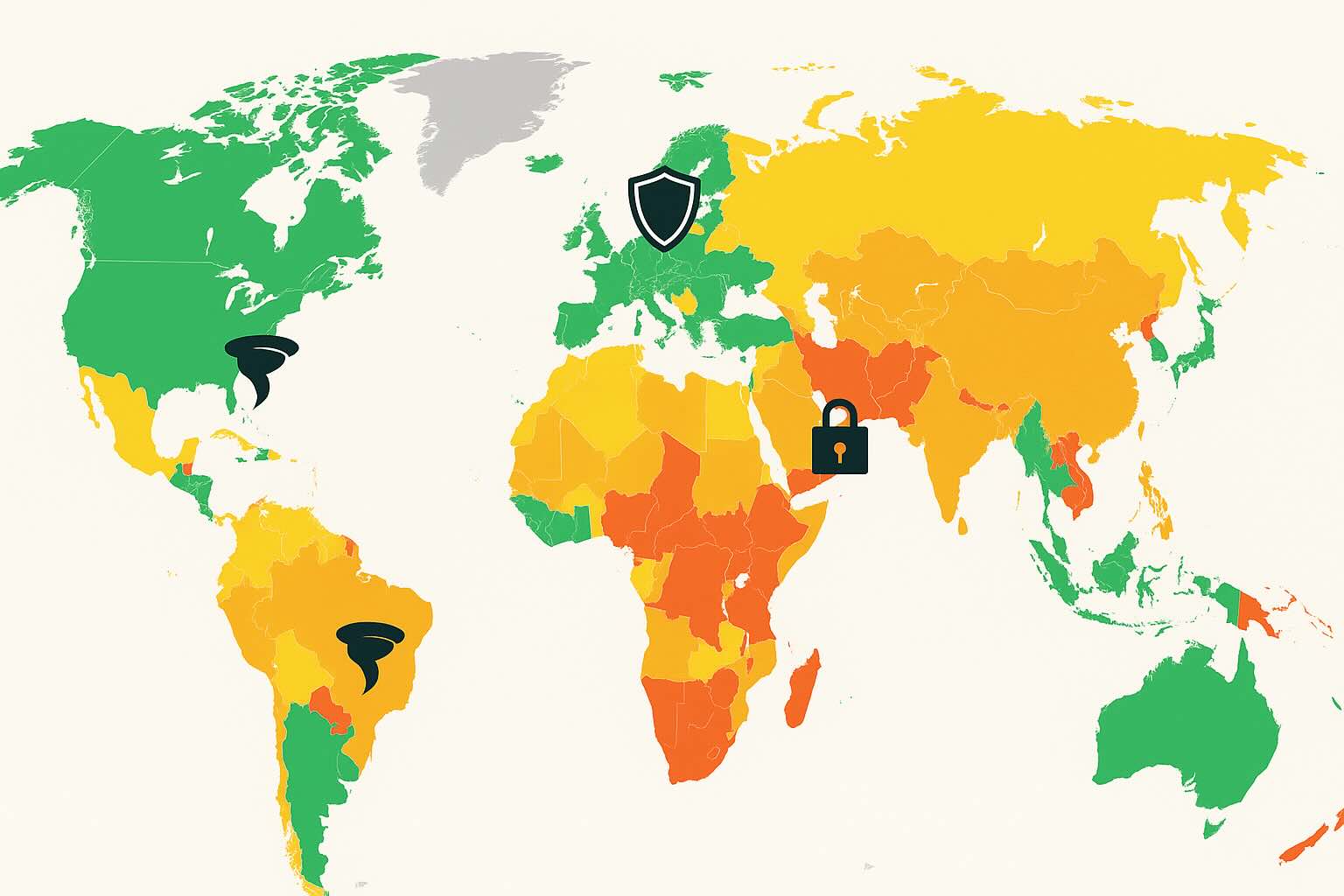

In an era of frequent natural disasters, pandemics, cyberattacks, energy shortages, war threats, and supply chain shocks, a nation’s preparedness can mean the difference between resilience and catastrophe. Governments worldwide have varied capacity to anticipate and handle crises, and citizens’ own readiness plays a role as well. This investigative overview examines which countries rank among the best prepared and which among the worst prepared across several crisis categories, using data from global indices like the Global Health Security Index, the INFORM Risk Index, and other resilience metrics. We also explore how public authorities’ planning and infrastructure, as well as civil defense and individual preparedness, contribute to national readiness.

(Threats requiring preparedness include natural disasters, disease outbreaks, cyber warfare, energy crises, military conflicts, and disruptions in global supply chains. Below we break down preparedness by each category, highlighting top and bottom examples.)

Nature’s fury whether earthquakes, hurricanes, floods, or wildfires tests a country’s emergency planning and infrastructure. The World Risk Index assesses disaster risk by combining hazard exposure with vulnerability and coping capacity. It consistently finds that developing and hazard-prone nations top the risk rankings. For example, the 2022 WorldRiskReport showed the Philippines as the country with the highest disaster risk (WRI ~46.8), followed by Indiaand Indonesia, due to their extreme exposure to hazards and relatively limited societal resilience. Other countries in the top tier of risk include Colombia and Mexico, underscoring that parts of Asia and Latin America face acute natural threat levels. In contrast, small wealthy states in Europe often enjoy the lowest disaster risk. Nations like Monaco, Andorra, or Luxembourg have minimal natural hazard exposure and strong infrastructure, placing them at the bottom of the risk index (with risk percentages well below 1%). These low-risk countries benefit from robust building standards, effective early warning systems, and ample resources for disaster response. In general, developed countries tend to have better preparedness for instance, building codes in earthquake-prone Japan or the Netherlands’ flood defenses whereas poorer nations with high hazard exposure struggle with inadequate infrastructure, leading to greater potential for a natural hazard to become a humanitarian disaster.

The COVID-19 pandemic starkly revealed gaps in global health emergency readiness. The Global Health Security Index (GHSI) rates countries on their capacity to prevent, detect, and respond to infectious disease outbreaks. According to the most recent (2021) GHS Index, no country is fully prepared the average global score was only 38.9/100, and even the top scorer failed to reach 80. The United States ranked 1st with the highest GHSI score (around 75.9), reflecting strengths like biomedical research and emergency response plans. Other high scorers included Australia, Finland, Canada, Thailand, and Slovenia, all in the upper tier of readiness. These countries tend to have advanced healthcare systems, disease surveillance, and vaccination programs. However, high ranking did not guarantee a perfect COVID-19 response for instance, the U.S. and UK were rated as most prepared yet struggled in practice. On the opposite end, the least prepared countries for pandemics are generally low-income states, especially in Central and West Africa. In the 2019 GHSI (similar in 2021), Somalia, Equatorial Guinea, and North Korea were among the bottom three, with scores in the teens out of 100. Many countries in this lowest tier lack basic health infrastructure, laboratory capacity, and emergency funds. The GHS Index findings led experts to warn the world remains “dangerously unprepared” for future pandemics. Indeed, all countries have gaps even top-tier nations must improve health system surge capacity and trust in public health guidance.

In our digitized world, cyberattacks pose a critical threat to national security and economy. Preparedness for cyber crises involves government cyber defense strategies, robust IT infrastructure, and public awareness. Data from the Global Cybersecurity Index (GCI) by the ITU and independent studies reveal a wide gap between the most and least cyber-secure countries. Denmark currently stands out as one of the safest and best-prepared countries against cyber threats. In a 2020 ITU assessment, top performers included the United States, United Kingdom, and France, all scoring around 0.92–0.93 on a 0–1 scale in cybersecurity commitment. Denmark’s success is also reflected in low malware infection rates; it was ranked #1 as the most cyber-secure country in a 2023 comparative study, placing in the top three of 15 security indicators (e.g. very low ransomware and cryptominer attack rates). On the flip side, several countries remain highly vulnerable. According to the same study, Tajikistan was the least cyber-secure country (ranked 75th of 75), followed closely by Bangladesh and even China in the bottom tier for certain cyber risk metrics. Tajikistan suffered high rates of malware and cryptomining attacks, highlighting weak defenses. These findings illustrate how some nations (often smaller or poorer ones) lack the resources and frameworks for cyber defense. However, the data also show no country is perfect even top-ranked countries have weaknesses (for example, a nation might excel in preventing outbound attacks but still see many citizens victimized by phishing). Overall, national cybersecurity preparedness is strongest in countries that invest in robust cyber policies, workforce training, and international cooperation, whereas those with limited digital infrastructure or governance issues lag behind in this modern battleground.

Energy crises such as fuel shortages or grid blackouts test a country’s resilience and planning. Preparedness in this domain means having diversified energy sources, strategic fuel reserves, and robust infrastructure. Some nations have proactively built energy security into their systems. For instance, Denmark leads the world in balancing energy needs with reliability and sustainability. In 2024 Denmark ranked #1 in the World Energy Council’s Energy Trilemma Index for its strong energy security, equity, and sustainability performance. Decades of investment in renewables (like offshore wind) and cross-border grid interconnections have given Denmark a stable supply and insulation from shocks. Other countries known for energy resilience include Norway (with abundant domestic oil/gas and hydro power) and France (nuclear power providing energy independence). By contrast, countries that rely on single sources or imports can face severe crises. A striking recent example is Lebanon, which has been plagued by an ongoing electricity crisis. In August 2024, Lebanon’s last running power plant ran out of fuel, triggering a complete nationwide blackout for over 24 hours. Hospitals, water systems, and even the main airport were left without state electricity, forcing reliance on private diesel generators. This collapse stemmed from years of mismanagement and lack of contingency fuel supplies. Similarly, several developing nations and remote island states remain highly vulnerable to energy supply shocks, as they depend on imported fuel and have limited emergency stocks. The contrast is stark: energy-secure countries maintain strategic petroleum reserves or diverse energy mixes (e.g. renewables, interconnectors), enabling them to weather global price spikes or embargoes, whereas energy-insecure countries can literally go dark when a crisis hits. The lesson is that investment in infrastructure, regional cooperation, and sustainable energy not only furthers climate goals but also builds resilience against sudden energy crunches.

The return of geopolitical tensions has put civil defense back in focus. Preparedness for war or military attack involves both the armed forces and the civilian sphere plans for protecting the population, continuity of government, and essential infrastructure under extreme duress. A few countries stand out historically for their robust civil defense measures. Finland is often cited as a model: it has spent decades preparing for the worst-case scenario of conflict with its giant neighbor Russia. As of 2023, Finland’s government tallied 50,500 bomb shelters nationwide enough sheltered space for about 4.8 million people (over 85% of its population). These shelters, many built into basements and tunnels, are equipped to withstand conventional attacks and even chemical or nuclear incidents. Finland’s comprehensive approach, which includes mandatory shelter construction in buildings since the 1950s, has yielded “one of the most credible civil defenses in the entire world,” according to security analys. Other countries with high civil readiness include Switzerland (famous for its extensive alpine bunkers and compulsory citizen military training) and Israel (where most homes have safe rooms and the populace routinely drills for attacks). On the other hand, many nations largely abandoned civil defense after the Cold War, leaving gaps today. Sweden is a telling case: it once had a gold-standard civil defense, but for years after 1990 it neglected those systems. By 2023, Swedish authorities admitted that the country’s civil preparedness was “not designed to handle an armed attack and the extreme stresses of war” plans, training, and stockpiles had atrophied to the point that a veteran described Sweden’s civilian defense as “basically non-existent”. This stark assessment has spurred Sweden to reinvest heavily in civil defense in response to Russian aggression. Many countries, however, remain even less prepared: those embroiled in internal conflict or with weak governance (e.g. parts of the Middle East or Africa) often lack any effective civil defense program, meaning civilians are extremely vulnerable in wartime. By contrast, countries that maintain high readiness (like Finland) have laws and infrastructure ensuring that in crisis, civilians have shelters, emergency supplies, and clear instructions for survival. The war in Ukraine has underscored that national resilience relies on both military strength and civilian fortitude as NATO’s Secretary General noted, “our militaries cannot be strong if our societies are weak”.

The COVID-19 pandemic and other recent shocks (such as the 2021 Suez Canal blockage) demonstrated how vital supply chain resilience is to national welfare. Preparedness here means diverse sourcing of essential goods, local production capacity for critical items, and logistical strength to adapt when global trade is disrupted. According to the FM Global Resilience Index which ranks countries on economic, risk quality, and supply chain resilience factors the most resilient business environments in 2023 were in advanced economies. Denmark again topped this index, followed by the likes of Singapore, Luxembourg, Germany, Switzerland, and the United States, all scoring highly on productivity, infrastructure, and risk management. These countries combine strong economies with robust logistics networks and low corruption, allowing them to absorb shocks. For instance, Singapore’s diversified import sourcing and efficient port infrastructure help ensure essential supplies keep flowing even during crises. Meanwhile, countries that are lower-ranked in resilience tend to have more fragile economies or unstable environments. The FM Index identified places like Dominican Republic and Lebanon among those that fell in resilience ranking, due to factors like climate risk and weak health. Generally, many low-income countries and small island states struggle with supply chain preparedness they may rely on one port or a narrow range of suppliers for food, medicine, or fuel. When a disaster or global upheaval strikes, these nations face severe shortages quickly. By contrast, the top resilient countries often keep emergency stockpiles (for example, Japan mandates strategic reserves of rice and petroleum) and have plans to ramp up domestic manufacturing of critical supplies (as seen when many Western countries invoked wartime production acts for medical gear during COVID-19). Supply chain preparedness is thus a function of good governance and foresight: nations that invest in reliability through infrastructure, diversification, and alliances can better withstand and recover from global disruptions, whereas those that do not are at the mercy of events.

Across all these domains, a common theme emerges: the countries most ready for crises pair strong government-led preparedness with engaged, informed citizens. Effective preparedness is a whole-of-society effort. Governments must build frameworks (from emergency stockpiles to response protocols), but citizens also need to be ready to act calmly and help themselves in an emergency. For example, Sweden’s “Total Defense” model explicitly includes both military defense and civil defense, with every resident expected to play a role in national resilience. In recent years Sweden has even re-issued a handbook If Crisis or War Comes to households, reviving Cold War-era guidance on everything from finding shelters to spotting misinformation. Public education and drills are vital: countries in earthquake zones like Japan regularly train citizens on evacuation and encourage home emergency kits. In Finland, a culture of preparedness is “instinctively understood” people take civil defense seriously without question, reflecting memories of past conflicts and comprehensive government messaging. This societal resilience can be decisive. As one report on the Ukraine war noted, “Ukraine has demonstrated the critical necessity of the population’s resilience and will to defend their nation.” Grassroots initiatives and civilian resolve in Ukraine helped keep the country intact in the face of invasion. Conversely, where public trust and engagement are low, even the best-laid government plans may falter. The Global Health Security Index highlights that many countries lack public confidence in government or fail to include communities in preparedness plans. Thus, the most prepared countries cultivate both top-down and bottom-up readiness: authorities invest in infrastructure and risk management and communicate transparently, while citizens are encouraged to stay informed, stock emergency supplies, and volunteer in trainings. This symbiosis builds true resilience.

In early 2025, a new initiative known as the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) began restructuring several federal agencies in the United States. While intended to streamline operations, it has raised major concerns among crisis management experts:

FEMA & NOAA Cuts: DOGE-led reforms have slashed budgets and reassigned personnel within FEMA and NOAA, potentially weakening America's ability to forecast storms, respond to disasters, or coordinate relief.

Digital Centralisation Risks: The consolidation of IT systems across federal agencies has led to fears that cyber vulnerabilities or mismanagement could paralyse emergency services.

Civilian Volunteer Programmes: Reductions in AmeriCorps and local volunteer networks risk undermining rapid response capacity during large-scale emergencies.

In a time of growing climate risks, cyber threats, and geopolitical uncertainty, DOGE’s influence could either streamline U.S. readiness or critically hamper it. While the U.S. ranks high in GHSI and historically strong institutional resilience, its preparedness could be tested if core agencies are hollowed out or over-centralised.

No nation is immune from crises be it a Category 5 hurricane, a novel virus, a cyber war, an energy crunch, or even armed aggression. However, as data and examples show, some countries have marshaled their wealth, governance, and social cohesion to become highly prepared, whereas others remain dangerously exposed. Generally, robust preparedness correlates with strong institutions, foresightful policies, investment in infrastructure (health systems, grids, shelters, etc.), and an involved populace. Poor preparedness often traces to underinvestment, instability, or complacency. Importantly, rankings can change: countries like Sweden that slipped in readiness are now scrambling to rebuild it, while others like Singapore relentlessly improve their resilience year by year. International indices such as the GHSI and INFORM Risk Index serve as benchmarking tools and a wake-up call. They remind us that even top-ranked nations have critical gaps to fix (as seen in the pandemic), and that lower-ranked nations need support to boost their crisis-response capacities. For expatriates and citizens alike, understanding a country’s preparedness landscape provides insight into how safe and supported one might be when disaster strikes. The ultimate goal for any country is to learn from the leaders and bolster its defenses both structural and social so that when the next crisis comes, it can respond swiftly, protect its people, and emerge resilient. In an age of converging risks, building a culture of preparedness is not an option but a necessity for survival and stability.

Sources: Global Health Security Indexworldpopulationreview.com ilearncana.com; INFORM Risk Indexpreventionweb.net; WorldRiskReporten.wikipedia.org; War on the Rocks (Sweden & Finland civil defense)warontherocks.com warontherocks.com; Reuters (Finland bomb shelters)reuters.com; Human Rights Watch (Lebanon blackout)hrw.org; Comparitech Cybersecurity Rankingcomparitech.com; FM Global Resilience Indexbusinessfacilities.com; Devex Global Health Security analysisdevex.com; NATO statements on resiliencewarontherocks.com.

Author

Sammy Salmela is a contributor to BestCityIndex with expertise in urban development and global city trends.

Stay updated with our latest insights and city rankings.

Introduction:The aroma of aged wheels, bubbling fondue, and freshly baked bread for cheese lovers, Europe is a true paradise. Here are five cities where cheese...

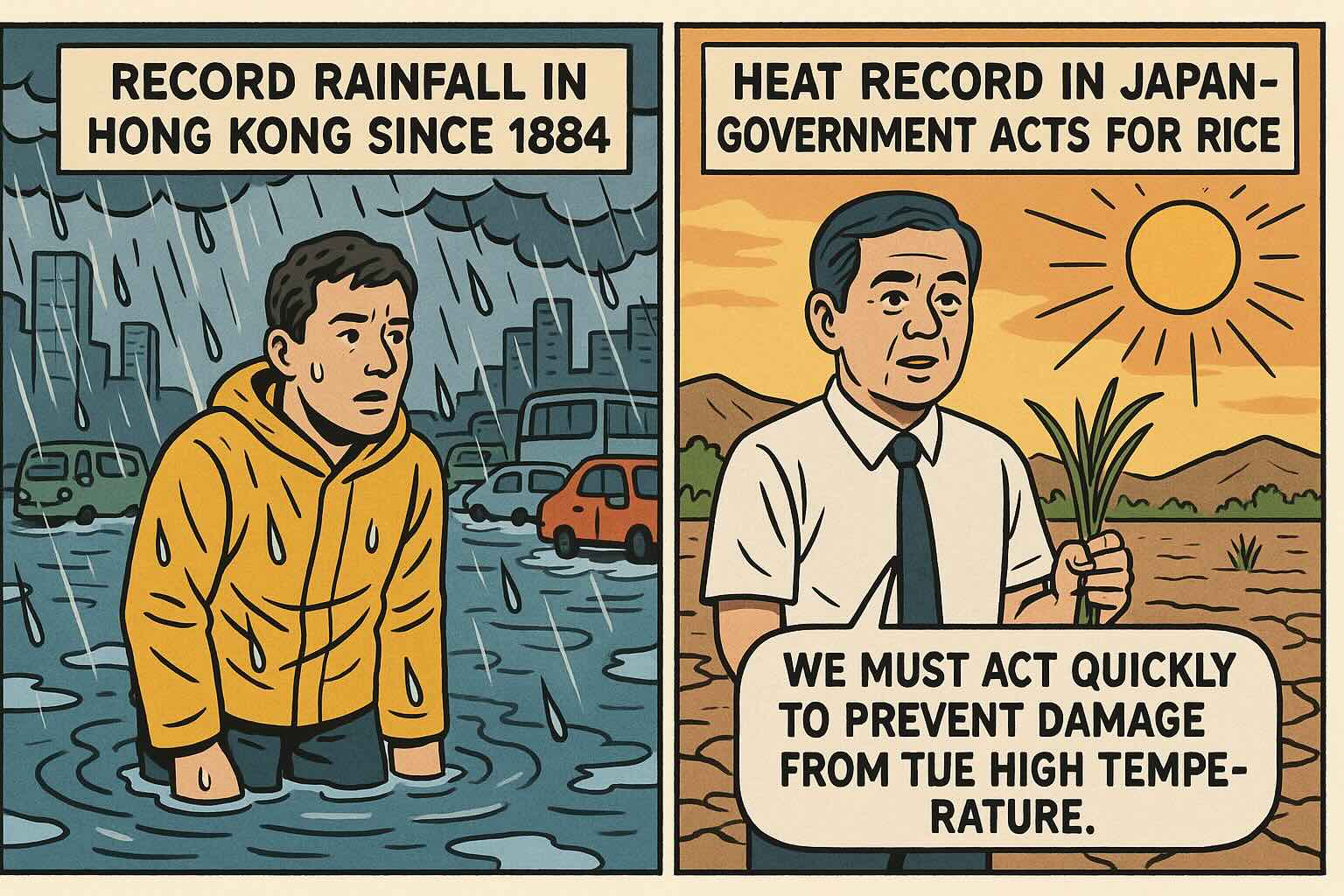

Date: 5 August 2025Source: AFP, Reuters, Local Weather AuthoritiesReading Time: 3 minutesIntroductionIn just one week, Asia has faced two stark climate...

Moving to Europe: Pros and Cons by Country for Work, Retirement, Education & Lifestyle Part 1.Moving from the United States to Europe is an exciting...